Home » Biographical » Reminiscences of the Swami (Page 3)

Category Archives: Reminiscences of the Swami

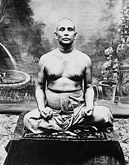

Swami Kripananda

“In the beginning crowds of people flocked to his lectures. But they were not of the kind that a teacher of religion would be pleased to have for his auditors. They consisted partly of curiosity-seekers who were more interested in the personality of the preacher than in what he had to preach, partly of the representatives of the cranky and fraudulent elements mentioned before, who thought they had found in the Swami a proper tool to forward their interests. Most, if not all, of this latter type tried to induce him to embrace their cause, first by promises of their support, and then by threats of injuring him if he refused to ally himself with them. But they were grievously disappointed.”

Mrs. Mary C. Funke

February l4th, 1894, stands out in my memory as a day apart, a sacred, holy day; for it was then that I first saw the form and listened to the voice of that great soul, that spiritual giant, the Swami Vivekananda, who, two years later, to my great joy and never-ceasing wonder, accepted me as a disciple.

Rev. H. R. Haweis

From his book “TRAVEL AND TALK” Published in 1897

By London CHATTO & WINDUS and NEW YORK : DODD, MEAD, & COMPANY

Cornelia Conger

Cornelia Conger, was the granddaughter of Mr. and Mrs. John Lyons, the Swami’s first hosts in Chicago in September 1893. She was six years old when she met the Swami and wrote of him in part:

Annie Besant

A striking figure, clad in yellow and orange, shining like the sun of India in the midst of the heavy atmosphere of Chicago, a lion head, piercing eyes, mobile lips, movements swift and abrupt –– such was my first impression of Swami Vivekananda, as I met him in one of the rooms set apart for the use of the delegates to the Parliament of Religions. Off the platform, his figure was instinct with pride of country, pride of race –– the representative of the oldest of living religions, surrounded by curious gazers of nearly the youngest religion. India was not to

A striking figure, clad in yellow and orange, shining like the sun of India in the midst of the heavy atmosphere of Chicago, a lion head, piercing eyes, mobile lips, movements swift and abrupt –– such was my first impression of Swami Vivekananda, as I met him in one of the rooms set apart for the use of the delegates to the Parliament of Religions. Off the platform, his figure was instinct with pride of country, pride of race –– the representative of the oldest of living religions, surrounded by curious gazers of nearly the youngest religion. India was not to

be shamed before the hurrying arrogant West by this her envoy and her son. He brought her message, he spoke in her name, and the herald remembered the dignity of the royal land whence he came. Purposeful, virile, strong, he stood out, a man among men, able to hold his own.

Mrs. Wright

VENGEANCE OF HISTORY

[At the end of August 1893, Swami Vivekananda stayed at Annisquam at the house of Prof. J. H. Wright. So astonishing a sight did Swamiji present in this quiet little New England village that speculations set in at once as to who this majestic and colourful figure might be. From where had he come? At first they decided that he was a Brahmin from India, but his manners did not fully conform to their ideas.] It was something that needed explanation and they unanimously repaired to the cottage after supper, to hear this strange new discourse. . . .

“It was the other day,” he said, in his musical voice, “only just the other day — not more than four hundred years ago.” And then followed tales of cruelty and oppression, of a patient race and a suffering people, and of a judgment to come! “Ah, the English!” he said. “Only just a little while ago they were savages, the vermin crawled on the ladies’ bodies, . . . and they scented themselves to disguise the abominable odour of their persons. . . . Most hor-r-ible! Even now they are barely emerging from barbarism.”

“Nonsense,” said one of his scandalised hearers, “that was at least five hundred years ago.”

“And did I not say ‘a little while ago’? What are a few hundred years when you look at the antiquity of the human soul?” Then with a turn of tone, quite reasonable and gentle, “They are quite savage”, he said. “The frightful cold, the want and privation of their northern climate”, going on more quickly and warmly, “has made them wild. They only think to kill. . . . Where is their religion? They take the name of that Holy One, they claim to love their fellowmen, they civilise — by Christianity! — No! It is their hunger that has civilised them, not their God. The love of man is on their lips, in their hearts there is nothing but evil and every violence. ‘I love you my brother, I love you!’ . . .and all the while they cut his throat! Their hands are redwith blood.” . . . Then, going on more slowly, his beautiful voice deepening till it sounded like a bell, “But the judgment of God will fall upon them. ‘Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord’, and destruction is coming. What are your Christians? Not one third of the world. Look at those Chinese, millions of them. They are the vengeance of God that will light upon you. There will be another invasion of the Huns”, adding, with a little chuckle, “they will sweep over Europe, they will not leave one stone standing upon another. Men, women, children, all will go and the dark ages will come again.” His voice was indescribably sad and pitiful; then suddenly and flippantly, dropping the seer, “Me — I don’t care! The world will rise up better from it, but it is coming. The vengeance of God, it is coming soon.”

“Soon?” they all asked.

“It will not be a thousand years before it is done.”

They drew a breath of relief. It did not seem imminent.

“And God will have vengeance”, he went on. “You may not see it in religion, you may not see it in politics, but you must see it in history, and as it has been; it will come to pass. If you grind down the people, you will suffer. We in India are suffering the vengeance of God. Look upon these things. They ground down those poor people for their own wealth, they heard not the voice of distress, they ate from gold and silver when the people cried for bread, and the Mohammedans came upon them slaughtering and killing: slaughtering and killing they overran them. India has been conquered again and again for years, and last and worst of all came the Englishman. You look about India, what has the Hindu left? Wonderful temples, everywhere. What has the Mohammedan left? Beautiful palaces. What has the Englishman left? Nothing but mounds of broken brandy bottles! And God has had no mercy upon my people because they had no mercy. By their cruelty they degraded the populace; and when they needed them, the common people had no strength to give for their aid. If man cannot believe in the Vengeance of God, he certainly cannot deny the Vengeance of History. And it will come upon the English; they have their heels on our necks, they have sucked the last drop of our blood for their own pleasures, they have carried away with them millions of our money, while our people have starved by villages and provinces. And now the Chinaman is the vengeance that will fall upon them; if the Chinese rose today and swept the English into the sea, as they well deserve, it would be no more than justice.”

And then, having said his say, the Swami was silent. A babble of thin-voiced chatter rose about him, to which he listened, apparently unheeding. Occasionally he cast his eye up to the roof and repeated softly, “Shiva! Shiva!” and the little company, shaken and disturbed by the current of powerful feelings and vindictive passion which seemed to be flowing like molten lava beneath the silent surface of this strange being, broke up, perturbed.

He stayed days [actually it was only a long weekend]. . . . All through, his discourses abounded in picturesque illustrations and beautiful legends. . . .

One beautiful story he told was of a man whose wife reproached him with his troubles, reviled him because of the success of others, and recounted to him all his failures. “Is this what your God has done for you”, she said to him, “after you have served Him so many years?” Then the man answered, “Am I a trader in religion? Look at the mountain. What does it do for me, or what have I done for it? And yet I love it because I am so made that I love the beautiful. Thus I love God.” . . . There was another story he told of a king who offered a gift to a Rishi. The Rishi refused, but the king insisted and begged that he would come with him. When they came to the palace, he heard the king praying, and the king begged for wealth, for power, for length of days from God. The Rishi listened, wondering, until at last he picked up his mat and started away. Then the king opened his eyes from his prayers and saw him. “Why are you going?” he said. “You have not asked for your gift.” “I”, said the Rishi, “ask from a beggar?”

When someone suggested to him that Christianity was a saving power, he opened his great dark eyes upon him and said, “If Christianity is a saving power in itself, why has it not saved the Ethiopians, the Abyssinians?”

Often on Swamiji’s lips was the phrase, “They would not dare to do this to a monk.” . . . At times he even expressed a great longing that the English government would take him and shoot him. “It would be the first nail in their coffin”, he would say, with a little gleam of his white teeth. “and my death would run through the land like wild fire.”

His great heroine was the dreadful [?] Ranee of the Indian mutiny, who led her troops in person. Most of the old mutineers, he said, had become monks in order to hide themselves, and this accounted very well for the dangerous quality of the monks’ opinions. There was one man of them who had lost four sons and could speak of them with composure, but whenever he mentioned the Ranee, he would weep, with tears streaming down his face. “That woman was a goddess”, he said, “a devi. When overcome, she fell on her sword and died like a man.” It was strange to hear the other side of the Indian mutiny, when you would never believe that there was another side to it, and to be assured that a Hindu could not possibly kill a woman. . . .

Vaikunthanath Sanyal

Source: The life of Swami Vivekananda by his eastern and western disciples

Ramakrishna period: 1885

Vaikunthanath Sanyal, a devotee of the Master, was at Dakshineswar, the day following the episode where Narendra, as instructed by Ramakrishna, went to the Kali temple intending to ask for boons of material prosperity and asked for spiritual boons instead.

Swami Vimalananda

BEFORE I knew Swamiji personally, I had heard much about his greatness from persons who had moved and lived with him on the closest terms of intimacy. Therefore, when it was announced in the year 1893 that he had gone over to America to represent our religion at the Chicago Parliament of Religions, I started following his movements with the closest attention and the greatest interest. I was anxiously waiting to see if his achievements would not confirm me in my very high estimate of him. I need not tell you, people of Madras, that every bit of my expectation was much more than satisfied. But till I saw him with my own eyes, the perfect satisfaction of knowing the man could not come. Till then I could not be quite free from the secret misgivings that I might be after all labouring under a delusion. So you see, gentlemen, that I did not meet Swamiji as one in any way biased against him. The throbbing interest and convincingness which attach to the glowing description of the conquest of opponents of a great man of overmastering personality does not belong to my subject. I may say, I was already a great admirer of his. But I must say at the same time that it was not too late in the day to retrace my steps and give Swamiji up as one unworthy of my love and esteem if facts were found to give the lie. Perhaps, the shock which such a disclosure would have given to my mind would be too painful; perhaps it would have cost a great drenching of the heart. But I can assure you that the instinct of moral self-preservation was yet stronger than my admiration of Swamiji, and cost how much it would, the heart could not long cling round him if reason and moral sense condemned him with one voice.

Swami Turiyananda on Vivekananda

Sri Ramakrishna did not allow everybody to practice the nondual aspect of meditation. What good is it to proclaim that you are one with the Absolute unless the universe has vanished from your consciousness? Sri Ramakrishna used to say: ‘You may say that there is no thorn, but put your hand out—the thorn will prick, and your hand will bleed.’ But with regard to Swamiji, Sri Ramakrishna said, ‘If Naren says that there is no thorn, there is no thorn; and if he puts out his hand no thorn would prick it, because he has experienced his unity with Brahman.” When Swamiji used to say, ‘I am He,’ he said so from his direct perception of the Absolute. His mind was not identified with his physical self.

Swami Shuddhananda

(Translated from Swamijir Katha in Bengal)

LONG years have rolled away, It was February 1897.I believe, when Swami Vivekananda set his foot inBharatavarsha (India) after his triumph in the West. From the moment when in the Parliament of Religions at Chicago Swamiji proved the superiority of the Hindudharma and left the banner of Hinduism flying victoriously in the West, I had gathered every possible information regarding him from newspapers and read them with great interest. I had left college only two or three years ago, and I had not settled down to earning. So I spent my time, now visiting my friends, now going to the office of the Indian Mirror, devouring the latest news about him and studying the reports of his lectures. Almost all that he had spoken in Ceylon and in Madras from the time he had set foot in India had thus been read by me. Besides this, I used to visit the Alambazar Math and hear from his gurubhais as well as from those of my friends who used to frequent the Math many things about Swamiji. Further, nothing escaped my notice of the comments concerning him that appeared in Bangabasi, Amritabazar, Hope, Theosophist, etc. — some satirical, some admonishing, some patronizing, each according to its own outlook and temperament.